THE ARAB HORSE IN SOUTH AFRICA

By Terri Weistra

The Arab is considered to be one of the very oldest and also one of the most true-blooded of all the known domesticated animals. Arab horses are depicted in early Arabian rock inscriptions dating back to 2000 BC. Both early Egyptian and Greek works show horses of undoubted Arab type and beauty. The breed has its origin in the deserts of Arabian and due to its isolation, was maintained absolutely pure for thousands of years. The nomadic tribesmen of the desert considered their mares the source of purity, and for this reason prized them far above the stallions.

The Arab is the ancestor of the Thoroughbred, Hackney and all other light breeds of horses. The Darley, Godolphin and Leeds Arabs are some of the famous sires founding the breed specialised to speed, whilst Old Bald Peg and the Royal mares of King Charles II provide the female Arab foundation.

During the nineteenth century Abbas Pasha I of Egypt acquired a stud of over 600 horses of the finest type and quality from the Arabian desert. In 1860 the stud was dispersed but the greater part was bought by Ali Pasha Sheriff. It was he who perpetuated the strains that appear in the Crabbet horses and in many American studs. No history of the Arab is complete without mention of Lady Anne and Wilfred Blunt, for it was their interest in the Arab that led to the collection of further specimens from the desert and drew the attention of the horse breeding world to the Arab Horse.

The Arab Horse Society of South Africa affiliated with the South African StudBook Association in 1961. Prior to this, Arab breeders made direct stud book entries. It is an unfortunate fact that of all the horses imported prior to 1940, not one left registered progeny. This is a great loss, as some famous horses were imported from Great Britain, the desert, Egypt and even from Argentina. Amongst those imported was the famous AZREK, imported by Cecil John Rhodes from the Crabbet Stud. On the farm "Achtertang" Capt. Gomer Williams had a well-established Arab Stud by 1910. His was one of several studs whose breeding and efforts are lost to us, but the infusion of Arab blood in what has today become known as the Boer Perd or South African Horse remains for all to see. Due to the Arabs antiquity, purity of blood, long and careful breeding over the centuries, he is the most prepotent sire amongst equines, and when beauty, stamina, endurance and quality are needed an infusion of Arab blood is usually resorted to. In fact the famous South African remounts known from earlier days and also the Basuto.

THE ARABIAN HORSE

Although the Arab Horse Society of South Africa was only recognised by SA Stud Book Association as the official Breed Society for the control of Arabian horse breeding in 1961, the breeding of Arabian horses in South Africa goes back many years.

The concept of a World Arabian Organisation was discussed internationally a mere eight years later in 1969 with the Arab Horse Society of South Africa taking an active part. WAHO (World Arab Horse Organisation) was officially registered as a charitable organisation in 1972 with South Africa being recognised as one of the seven founder nations with its StudBook totally accepted. This illustrates the respect in which the S.A.S.B. is held internationally. South Africas Arabians were now with the giants of Arabian breeding; USA, UK, Poland, The Netherlands, Egypt, Australia and New Zealand.

The sole object of WAHO is the maintenance of the purity of the Arabian breed. It is a non-profit making body with all its executives working without reimbursement for either travel or subsistence. Their offices are now located in London. South Africa still has one executive member on its board.

Today with the new breeding techniques of Transported Semen and Embryo Transplants, strict controls are essential. The US-Registry pioneered all modern breeding techniques and made rules to control them carefully so as to maintain purity. WAHO and its members have wisely accepted these rules and regulations.

During the early days of WAHO, South Africa tried desperately to have the embargo on the export of our Arabians lifted. After many years of struggle, international export restrictions have become less restrictive. In our isolation we maintained the highest standards and maintained much sought after bloodlines.

WHAT AN ARAB SHOULD LOOK LIKE

By: Charmaine Grobbelaar - reprinted from Guidelines.

The emphasis in an article of this nature is on the word SHOULD. When breeding or judging Arab horses (as with any other breed of livestock) one tries to become familiar with the picture of the perfect animal. Therefore, when describing a particular breed it is always perfection or the ideal which is put into word. As the perfect animal does not exist, when looking at the animal the basis which one tries to achieve is a balance between the various points (described below), then summing up the whole.

There is nothing modern, or new, about the looks of an Arab horse. In other words, the same breed characteristics we look for today have existed for centuries. It is important to the present day breeder of the Arab horse to try and preserve this horse, which is a living classic treasure.

The HEAD is a breed characteristic and it is far more important than in other breeds of horses. Ideally we have a pronounced forehead, and the profile from below eye level concave - this is often referred to as the dish-face. The eyes should be placed low in the head; they should be round, large and set well apart. Around the eyes the skin is black and bare of hair and is often referred to as painted eyes. This reminds one of the ancient and modern use of eye shadow. The HEAD is a breed characteristic and it is far more important than in other breeds of horses. Ideally we have a pronounced forehead, and the profile from below eye level concave - this is often referred to as the dish-face. The eyes should be placed low in the head; they should be round, large and set well apart. Around the eyes the skin is black and bare of hair and is often referred to as painted eyes. This reminds one of the ancient and modern use of eye shadow.

The JAWS (or cheeks) are large and round, wide apart where they join the neck. A good Arab head is beautifully moulded with no fleshiness or coarseness. It is comparatively short and will taper to the muzzle that should be very refined. Nostrils are soft and flexible and can extend unbelievably; this affords free passage of air when needed. Ears should be finely chiselled and full of life. Cheekbones should be finely chiselled and prominent.

Where head and neck meet one another, it should be clean cut. Although well muscled the neck should not be short in relation to the body, the Arab horse can really arch their necks. The curve of the throat and neck is most important.

They should have good wither, not knify or low and loaded.

SHOULDERS should be well placed and sloping. The back short, the ribs barrel shaped and we want good depth through the body. Quarters long and muscular as this is the driving force and a horse must be able to get his hocks under him to propel him forward. Croups should be comparatively horizontal or level, this does not mean they should be flat; the length of the croup is important. Limbs must be good. Long well developed forearms and gaskins. Knees flat, hocks placed well down. The cannon bones are short and of ivory density with tendons well defined and like bow strings. Artists of the late 18th and 19th centuries must have been most impressed by these fine characteristics so that they often over emphasised these points as well as the strong sloping pasterns.

The CHEST should not be narrow, but developed with enough heart room.

As important as the head is the tail carriage. The Arab is the ONLY breed that has this natural tail carriage. While standing the tail is not "carried". When the horse starts moving at a walk the tail is lifted away from the body. The faster the movement, trot and canter, the higher the tail is lifted. When excited or just enjoying themselves, they will often throw the tail right over their backs and even keep it there for a few moments when coming to a standstill. There is something very gay and gracious about the tail carriage, and it is the envy of many owners of other breeds, who go to great lengths to imitate it. As important as the head is the tail carriage. The Arab is the ONLY breed that has this natural tail carriage. While standing the tail is not "carried". When the horse starts moving at a walk the tail is lifted away from the body. The faster the movement, trot and canter, the higher the tail is lifted. When excited or just enjoying themselves, they will often throw the tail right over their backs and even keep it there for a few moments when coming to a standstill. There is something very gay and gracious about the tail carriage, and it is the envy of many owners of other breeds, who go to great lengths to imitate it.

Arab horses should be shown with full manes and tails. Manes are not clipped or braided or plaited. This of course does not mean that when competing in open competitions under saddle it would be incorrect if the mane was plaited. Partbreds and Anglo Arabs are often shown with plaits.

Colours usually are chestnut, grey, bay and sometimes brown. Grey includes from nearly black in colour in young horses to pure white in older ones. Foals are never born grey, but either chestnut, bay or nearly black; they change colour as they become older and there is not a set pattern (or length of time) for this colour change. Some are beautifully dappled, other flea-bitten and others an astonishing roan or pinkish colour.

The skin is always black except under white markings. White face markings, leg markings and sometimes body spots are found throughout the breed.

To say that you own an Arab is to tell a half-truth. The other half is that the Arab horse owns you. You have chosen and been chosen. You have been privileged to receive in wonderfully generous measure and it is your duty to give in the same measure. The bond between horse and man is part of a much wider bond; you are committed in an unwritten contract to all Arabian horses, owners, breeders and enthusiasts in your own country and indeed, in every country in the world in which the hoofbeat of the Arabian horse sounds.

INTRODUCTION TO COLOUR MARKINGS OF THE ARABIAN HORSE

The purpose of this publication is to help Arabian horse owners understand the definitions of coat colours, markings etc., on the Arabian horse. The description listed on the Registration Certificate should identify each individual horse for life. This is why it is extremely important for owners to carefully draw their horses markings correctly the first time. As the horse ages, there is always a possibility that it may become lost or mistaken for another horse. One of the primary means of identifying Arabian horses is by their markings as described on the Registration Certificate.

Arabian owners take pride in the fact that Arabian horses are the purest of all breeds. It is the responsibility of the Arabian horse breeder to protect and maintain that purity of bloodlines. This can only be done through accurate record keeping and proper identification of each individual Arabian horse.

MARKINGS: TRUE AND FEINT

Markings are defined as configurations of solid white hairs contrasting with the surrounding coat colour. "True" white markings grown from pink skin. Markings which grow from dark skin are described as "feint" markings. This distinction is particularly important on grey horses which grown lighter in coat colour as they age, often disguising white markings. Pink skin is a permanent identifying mark.

All white markings should be recorded on the Birth Notification application form, and on grey horses a distinction must be made between "true" and "feint" markings. If your horse is grey, you must complete boxes for underlying pink skin on the markings form. Pink skin is easier to identify if the coat is wet or shaved.

When you draw markings, secure your horse in front of you so that you can get all of the details. Dont try to do it from memory. Draw only (do not colour in) the outline of the white markings. Do not draw black points on a bay horse. Remember, your drawing will become a part of the horses permanent record. Be precise!

UNDER THE FOAL COAT:

CLUES FOR GETTING THE RIGHT COLOUR

The following are the coat colours: bay, chestnut, grey, black and roan. Most Arabians are registered as foals between the ages of two and six months. Sometimes, this makes it difficult to correctly specify coat colour on the Birth Notification application because foals are usually born chestnut, or dull bay and change colours after losing their foal coats.

There are clues, however, to help owners determine what colour a foal will be. Here are a few helpful hints:

- Most foals will begin to lose their fuzzy baby hair around the eyes and nostrils and the root of the tail first, followed by the legs. Check the colour of the smooth hair in these areas. Usually, that will be the foals permanent colour.

- If white hairs appear on any area of the face, the foal will usually be grey. Some horse owners say that if there are white or grey hairs on the foals eyelids and if that foal has at least one grey parent, the foal will be grey.

- If the foal coat is replaced by black hair on the legs, the foal will usually be bay.

- If the foal coat on the legs is replaced by chestnut hair, and the foals mane and tail are not black, the foal will usually be chestnut.

- The rule of genetics followed is that the mating of two chestnuts always results in a chestnut foal.

- Another rule of genetics followed is that a foal will never turn grey unless one parent is grey.

Commonly, a horse that will be black is born a mousy grey colour and a foal that is born looking black will not stay that colour.

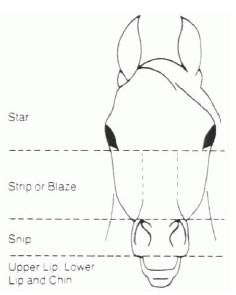

FACIAL MARKINGS

For the purpose of Registration, facial markings will be described as follows: For the purpose of Registration, facial markings will be described as follows:

Star Any white markings occurring above the eye line.

Strip Any white marking occurring below the eye line and above the top of the nostrils but within the nasal bones.

Blaze Any white marking occurring below the eye line and above the top of the nostrils and extending outside both nasal bone lines.

Snip Any white marking occurring between the top of the nostrils,

and the bottom of the nostrils.

Upper Lip Any white marking occurring below the nostrils, but still on the upper lip.

Lower Lip Any white marking occurring on the lower lip.

Chin Any white marking occurring below the lower lip.

LEG MARKINGS

Be sure to draw all markings exactly as they appear on your horse (same shape, same location).

If a leg marking is indicated, hoof colour must be checked. It is assumed that all markings originate from the coronet band.

Coronet White markings extending no more than one inch above the coronet band.

Pastern White markings anywhere between the coronet marking and the bottom of the fetlock joint.

Fetlock White markings extending above the pastern, but below the top of the fetlock joint.

Sock White markings extending above the top of the fetlock, but below the mid point of the cannon.

Stocking White markings extending above the mid point of the cannon.

Ermine Markings These are small black marks which sometimes appear around the coronet band. It is not necessary to draw these on the application form, but they should be described on the form in the area provided for body markings.

"PARTIAL" LEG MARKINGS

If a marking extends to a designated part of the leg only partially, the description of the markings with the word "partial" should be reflected on the Registration application (such as "partial fetlock") On the application form, owners should carefully draw markings in the same location and shape as they occur on the horse. Accurate drawings will show any partial markings.

BODY MARKINGS

A written description of any unusual body markings, noting colour, size, shape and location should be included on the application form. Draw only white markings on the form. While the written descriptions may not appear on the Registration Certificate, they will become part of the horses permanent record, and may be helpful should questions of identity arise.

Body markings usually fall into four categories: 1) dark patches on a bay or chestnut; 2) grey or roan patches; 3) white marks (these should be drawn in); 4) and discernible scars.

Brands, tattoos or freeze marks should also be recorded, noting design and location.

HOOF COLOUR

For Registration and identification purposes, hoof colours should be recorded as follows:

Dark hoof - Black or dark in colour. Normally, there will not be a marking above a dark hoof.

White hoof - White or light in colour. Normally, there will be a marking above a white hoof.

Parti-coloured hoof - a hoof that shows white and dark areas in stripes or larger areas.

ormally, there will be a marking above a parti-coloured hoof.

Front Page graphics by kind permission Stacey Mayer (USA)

FIND MORE INFO ON: http://www.arabhorsesa.co.za/

MORE ARTICLES: Click here to get more articles - a wide range of them in fact

|